- Home

- Scottie Jones

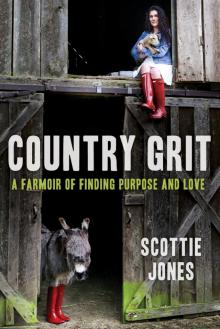

Country Grit: A Farmoir of Finding Purpose and Love

Country Grit: A Farmoir of Finding Purpose and Love Read online

Copyright © 2017 by Scottie Brown Jones

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jones, Scottie Brown, author.

Title: Country grit : a farmoir of finding purpose and love / Scottie Brown Jones.

Description: New York, NY : Skyhorse Publishing, [2017]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015225 (print) | LCCN 2017018539 (ebook) | ISBN 9781510722156 (ebook) | ISBN 9781510722149 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Farmers--United States--Biography. | Autobiography.

Classification: LCC S417.J66 (ebook) | LCC S417.J66 J66 2017 (print) | DDC 630.92--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015225

Cover design by Erin Seaward-Hiatt

Cover photo by Kristi Crawford

Author photo by Shawn Linehan

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

Introduction

PART ONE

PART TWO

Photo Insert

PART THREE

PART FOUR

PART FIVE

Epilogue: Stay on the Farm

Addendum: A Primer on Farming

Acknowledgments

For Caitlin and Annie, who may have questioned our sanity at moving to a farm but not the adventure.

INTRODUCTION

This book began as a series of letters to friends back home. Well, some would call them letters; anguished cries for help might be another interpretation. My friends found my pain completely amusing and suggested that I turn the letters into a blog, which then morphed into a book. That should explain why this reads like a crossbred blog-book.

Country Grit is constructed around a series of vignettes that are absolutely true—if we’re speaking of my experience. If we’re speaking of objective facts, you should know all the characters are composites. Please don’t come to my little town and expect to meet any of the characters in this book, because they don’t exist. That’s why I say the experiences I report on are real, just not the people. The real people in the real town I live in value their privacy and don’t take kindly to strangers poking at them.

While researching this book, I found there are hundreds of farm memoirs. So many, I felt it deserved its own genre, hence the term: farmoir. It amazed me how similar the experiences were in each of these books. I considered that someone, possibly one of my siblings who were always jealous of my demure charm, leaked my letters, leading to hundreds of cases of plagiarism. Except the farmoirs go back nearly a century, just about the time Americans began moving off the farm and into cities in large numbers. So besides the funny animal stories, there is something more going on here, some nostalgia for what was left behind.

Urban life leaves us with a hunger for the rural life and its connection with the natural world. This hunger encourages romantic visions of rural life leading to a kind of delusional thinking. My farmoir chronicles the undoing of those delusions, including the destructive consequences that follow whenever we ignore reality. Anyone who has started a new enterprise or made a radical change in their life will find parallels in my story. It always starts with a dream of how we hope our new life will be, and then reality intervenes. We are challenged, and as a consequence we are changed. While there are similarities shared by any new undertaking, there is something special about farming that lends itself to romanticism, and an extra degree of delusional thinking, that brings this process into sharper focus. See if you agree.

The reality of farming is business. Throughout the book I offer insights into the economics that drive the business of farming. Admittedly it’s pretty dry stuff, but hugely important since the business of farming ensures that you will eat today and tomorrow. The wealth of a country is built on its farming and especially on the efficiency of its farmers. It touches all of us every day, and so it’s good citizenship to know something about the business of our food supply. Frankly, I’m surprised it isn’t part of a standard high school education. For those who really want to wonk out on agricultural policy (and God bless you if you’re one of them because we need you), I’ve included a little addendum. I owe an immense debt to the real scholars: Paul Conkin (A Revolution Down On The Farm); David Danbom (Born In The Country); and Daniel Imhoff (Food Fight).

A number of friends lent their assistance to this project, including: Max and Dave Hanson, Karen and Allan Six, Craig Zaffaroni, Bert Banton, Linda and Ken Worley, Matt and John Clark, Mary and Steve O’Brien, Tanya Freeman, Nancy and Paul Cooke, Carolyn Avery, Russ Kaufman, Larry and Shirley Cole, Chuck and Lisa Smith, Mike and Liz Behrenfeld, Janet and Rolfe Hagen, and Curtis Koenig.

My other debt is to my family, whose patience and support made this possible. I’m speaking of my two daughters, Caitlin and Annie, but most importantly, my husband and collaborator, Greg, who provided extensive writing, research, and editorial assistance in this undertaking. And, of course, my grandson, Henry.

And with that, here’s my story, such as it is.

PART ONE

THE BEGINNING

Let me begin with a simple truth: I was not born to be a farmer.

I was born to the manicured lawns of suburban Connecticut. My father, in his daily commute to New York City, never dreamed of his little girl knee-deep in mud, wrestling sheep for a living. The years of boarding school and the advanced degree in art history did not prepare me for the agricultural life. I am presently a farmer by dint of circumstance—call it a karmic accident. Someone threw a switch and my life went barreling down an entirely different track. And that someone was my loving spouse—might as well name names. Call it karmic because I chose him. Call it accident because … well, I’m getting to that part.

Men are itchy creatures—and never more itchy than when life is most content. So, as my husband was reaching the zenith of his career as a psychologist he became the most discontent. Every aspect of our life together was a little too much or not quite enough for him, as he searched for targets that would reflect his discontent. I took to walking around him with my invisibility shield up, which wasn’t hard. Our lives were defined by well-rehearsed roles that kept us invisible to each other most of the time.

In fairness, my husband had a lot of help with his discontent. It was not an easy time to be a practicing psychologist. The crushing weight of managed health “cost” was turning sensitive caregivers into beleaguered accountants. Hours on the phone arguing care with insurance gatekeepers arguing costs left him deflated. He would say the profession he had dedicated his life to, and found so rewarding, had changed beyond his recognition. I would say men are itchy creatures.

For my part, I was happy in my work managing the retail end of a large urban zoo. I was responsible for a diverse set of income streams: the gate, gift shops, conce

ssions, special events, and such. Each day brought new challenges—financial pinches, marketing glitches, and mechanical breakdowns. And each problem came with a disparate set of personalities to bridge. When it became too much, there were always the animals. Just across the fence, the animals’ uncomplicated presence lent a grounding perspective to whatever problem was vexing me at the moment. Looking back, I was already in training for my next career. Mechanical breakdowns, teeth-grinding finances, marketing, and the animals—it’s all there in farming, with a lot fewer resources to get the job done. After all, it takes a lot of people to run a zoo.

Our home life was dominated by our work life. It wasn’t exactly bad, just compartmentalized. We were two high-functioning professionals in the urban-industrial, twenty-first century American experience. Both our children had recently matriculated to college, leaving us more time to pursue our careers. The models of efficiency we utilized at the office carried over to our chores, hobbies, and friendships, meaning we were very productive and rather affluent. We were also leading separate lives—separated by the compartments we created and the efficiency we expected. Lives that left us feeling vaguely lonely and disconnected in a multitude of ways that were hard to define without appearing whiney or ungrateful.

The next part of the karmic collision was contributed by the city itself. Rising from the desert, Phoenix was the source of plentiful jobs, cheap housing, and epic sprawl. There are no easy commutes in Phoenix, which is to say, there are no good starts to the day. For a third of the year the temperature exceeds 100 degrees. Commuting in that advanced state of swelter involves sitting in a carbon-belching, coffee-stained, bank-owned, all-terrain-cubicle, in eight lanes of gridlock, with direct sun baking you like truck-stop beef jerky. It follows that your thoughts turn to places you’d rather be—places that are cooler … greener … wetter. Please, God, a little wetter, with that faint promise that life can renew.

The final part really was inevitable. The other car crossed the line, demolishing our Acura, almost demolishing my husband, and ruining the day’s commute. He survived but lost the use of his left hand. There would be months of rehabilitation. That meant months with little else to do but ponder all the parts that itch. He began an online affair with real estate, staying up late, staring at the computer screen, and conjuring a new life. Once conjured, he began to fact-check. Being a diligent researcher, this went on for months. He called it testing the hypothesis to reach an informed decision. I called it scratching the itch.

For my husband, the violence of that terrible day stripped away his “suburban pretense.” It was not more things we needed, not more “stuff,” but more of a connection to life itself. We needed to live more simply—in harmony with nature. We needed to get back to the land. We needed to get back to each other.

I had to admit, I kind of liked the sound of that last part.

If you Google “cool, green, wet,” as my husband did, the first pop is likely to be the coastal mountains of Oregon. Eighty inches of rain annually keeps it wet. Moderating influences of the Pacific Ocean keep it cool, never cold or hot. Towering doug-fir forests keep it majestically green. And that, roughly, is how you get from lucrative careers with comfortable lifestyles in Phoenix to a sheep farm tucked into a slot valley in the Coast Range of Oregon. Well, that and just the right amount of delusional thinking.

Most people recruited to farming come with romantic delusions about the rural life. That’s as true for the original trekkers of the Oregon Trail as it is for the latest back-to-the-land neophytes. Without the romance, there would be no new blood in farming. Of course, the irony is that nothing will cure those delusions faster than the act of farming. Nature is both relentless and unforgiving. After five years, the delusions are gone and so too are a good many of the once-hopeful recruits. What remains depends on your answer to that most basic of questions: what gives meaning to life? What follows is my account of our first five years—those years that test and reveal.

BEGIN BY ENDING

When you’re twenty, adventure begins by throwing your bags in the back of the car. A quick glance to your partner, adjust the mirror, buckle up, and hit the gas. Life, like that open road, is in front of you. That’s how we got to Phoenix.

At mid-life, it’s more complicated. An adventure must be worked through in the movie theater of your mind until there is a story you’d pay to see. Once it’s worked through, you’re willing to sell tickets to it—promote it to everyone. Of course, having now paid for and promoted it, you’ll find the tickets are to an entirely different movie. At least that’s how it appeared to us, judging by the reactions of our family and friends. While we expected trumpets and Goldwyn’s lions announcing our mid-life movie, or at least a majorette with sparklers on her twirling baton, that’s not what we got.

The reaction began with our children, young adults vested in colleges as far from us as they could get. Our adventure was their betrayal. The house they couldn’t wait to leave was now the sacred shrine of all their childhood memories. We were the curators they had entrusted to keep it safe. Instead, we sold it to the philistines on the cheap. They were not even consulted! Well, not sufficiently enough to believe their parents were serious.

And they were right. With the children gone we had begun to think of ourselves as a couple, and the last time we were a couple, we were twenty. Throw the bags in the car and hit the gas.

It continued through our extended family and friends. The same people who suffered through Phoenix summers, complaining of gridlock, dreaming of an escape, now asked, “How could you?” instead of, “Save a place for me.” Of course they did. Our adventure was their loss. And their loss ultimately was our loss too.

At mid-life, adventures begin with endings. That’s because we don’t age by becoming set in our ways as much as we become set in our relationships. Each year adds another layer to the network of support we all depend on. By mid-life, our social fabric is so tightly bound that any tear caused by a prospective move would, if properly measured, scuttle most mid-life transitions. In our material world, it’s often the value of relationships we underestimate. A simple economic formula can decide whether you take or leave the sofa or box springs, but relationships always stay. Always. Relationships exist in a certain time and place and there they remain.

As painful as this truth is, it is not a reason to stay. Change is inevitable—even for those relationships that remain in place. To not heed the call to adventure has its price too and must be measured. Regret can shrivel lives and stunt relationships.

And so we said our good-byes, comforted by the thought that although our relationships would stay behind, our memories were portable. Not only portable, they were selective as well. Going forward, we would carry the memories of everyone who loved us and all that we loved. Just as farmers hold back their best seed for next year’s crop, we selected only the best memories to nourish our relationships. Memories, properly nourished, take root in our daily action, becoming part of who we are. We were not a young couple; we were mid-life with lots of memories. And, thanks to modern communication and transportation, there would be opportunities to refresh those memories. Your family and friends may not move with you but they will visit.

The final good-bye was for ourselves, or more accurately, for our “selves.” Every move involves the sorting of stuff, and each micro-decision asks you to define the new you. Throw out the business suits and keep the T-shirt, you’re going to a farm. But the black cocktail dress was so elegant and I only wore it once! What parts do you keep for the new you that has yet to emerge? It doesn’t matter, because it’s only a guess. We will always be wrong. Like the pianos discarded by the side of the Oregon Trail, the journey will decide for us.

But, if ever you come upon a farmer in a black cocktail dress, feeding her chickens—consider she may not be crazy, just transitioning.

OREGON GREEN

An hour past dawn and the temperature was already spiking above 80 degrees, dashing our hopes of makin

g it off the desert floor before the bake set in. We traveled not by car but by caravan—each vehicle had a position, a mission, and a shortwave radio. June is an auspicious month for new beginnings, and the beads of sweat only polished our resolve. Oregon—cool, wet, and green. Part mantra, part sacred promise.

I drove point. My job was to scout the various pit stops and report on the road ahead. My companion was Bezel, a crotchety old cat who complained incessantly. Greg, my husband, piloted a land-barge of a truck piled with stuff and trailering our two steeds: Chaco and Mora. Our two girls, Caitlin and Annie, drove behind the trailer making sure its anxious occupants were not creating problems. Assisting them with navigation, air flow updates, and squirrel sightings were our dogs, Patches (the good dog) and Cisco (the bad dog).

The adventure was underway. I couldn’t help but wonder at possible similarities between our caravan and the original Oregon Trail trekkers. Like Greg, they must have been full of hope for the future, but I wondered if some of the children were resistant like ours. Our oldest, Caitlin, had adopted an adversarial attitude while Annie remained disengaged. I was attempting to persuade the girls to stay open to the experience. I doubt that nineteenth-century trekkers dealt with vocal objections from their children, but I bet the tensions were there just the same.

Of course, the similarities end there. The historical trek entailed months of hardship and deprivation, delivering the family into a scenario of enforced cooperation to survive. Our girls would be back in college at the end of summer.

The shortwave buzzed, asking me to adjudicate their squabble over music selections. My children had an abundance of choices and none of them related to their survival. These were twenty-first-century girls learning to use their voice. I suggested they had the resources to solve it themselves. It’s challenging to keep the bonds of family when there are so many choices.

Country Grit: A Farmoir of Finding Purpose and Love

Country Grit: A Farmoir of Finding Purpose and Love